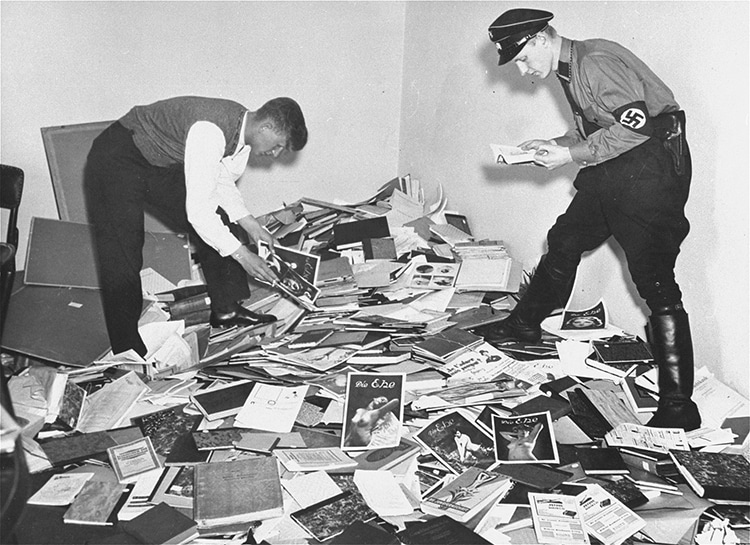

Nazi students picking through the collected materials of Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld, director of the Institute for Sexual Science in Berlin on May 6, 1933 in preparation for a book burning. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, Public domain)

Helen Keller is known for her activism for the disabled community. After a childhood illness rendered her deaf and blind, she learned to read, write, sign, and speak. Graduating Phi Beta Kappa from Radcliffe College in 1904, Keller was the first deafblind person to earn a Bachelors of Arts degree in the United States. A writer, a socialist, and a suffragette, her activism extended far beyond the deafblind community to touch many national and world affairs. Powerfully, in 1933, Keller penned an open letter in The New York Times warning Nazi students—who were openly burning books, including her own—of the perils of the fascist desire to crush opposing ideas.

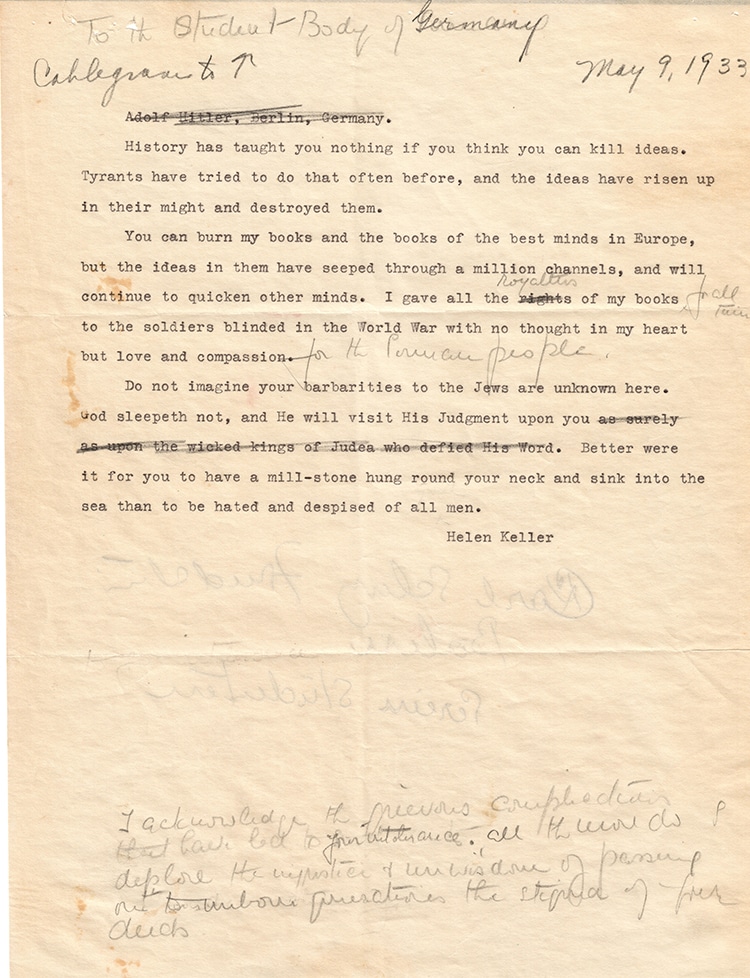

The letter can be seen in a typed draft by Keller from May 9, 1933. It contains handwritten additions from Keller's aid Polly Thompson. Keller's book, How I Became a Socialist, had been earmarked for burning on a long list made by the Nazi party for a mass burning event on May 10, 1933. On that day, university students participated in burnings across Germany. The 25,000 books burned targeted a variety of topics, from socialist works like Keller's to Freud to science fiction like H.G. Wells. While anything deemed “un-German” or antithetical to the Nazi regime was in danger, the burnings were heavily targeted towards the works of Jewish authors.

Keller for her part was aware of this attack's anti-Semitic focus. “Do not imagine that your barbarities to the Jews are unknown here,” she wrote in her open letter. Her letter, shared below, speaks to the power of ideas and the impotency of the fascist response to destroy and suppress. While incredibly dangerous, such responses cannot kill ideas which have already permeated the ether of society. Her words, while spoken 90 years ago and directed at a foreign nation, are worth remembering today, as books are banned from school libraries or pulled from public shelves for describing the experiences of people of color and LGBTQ+ individuals. History, as always, must prove a lesson—even as book banning parties would try to rewrite it.

In 1933, Helen Keller wrote an open letter in The New York Times to Nazi students, warning them of the perils of trying to stamp out ideas.

Helen Keller in 1920. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 4.0)

Keller, a socialist, paints a bleak picture of the fascist desire to stamp out ideas.

Helen Keller's own draft of the 1933 letter she wrote to Nazi students. (Photo: Internet Archive)

Here is the text of Helen Keller's Letter:

To the student body of Germany:

History has taught you nothing if you think you can kill ideas. Tyrants have tried to do that often before, and the ideas have risen up in their might and destroyed them.

You can burn my books and the books of the best minds in Europe, but the ideas in them have seeped through a million channels and will continue to quicken other minds. I gave all the royalties of my books for all time to the German soldiers blinded in the World War with no thought in my heart but love and compassion for the German people.

I acknowledge the grievous complications that have led to your intolerance; all the more do I deplore the injustice and unwisdom of passing on to unborn generations the stigma of your deeds.

Do not imagine that your barbarities to the Jews are unknown here. God sleepeth not, and He will visit His judgment upon you. Better were it for you to have a mill-stone hung around your neck and sink into the sea than to be hated and despised of all men.

Her words on learning from history, and the resilience of ideas against oppression, can certainly have modern meaning.

The Empty Library at the Bebelplatz in Berlin, designed by Micha Ullman. The sculpture is a memorial to the book burnings of Nazi rule. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 3.0)

No comments:

Post a Comment